Teaching Old English on YouTube: When a medieval language meets a modern medium

How do you make effective educational clips and what happens when you share them on YouTube? In this blogpost, Thijs Porck discusses the rationale behind his own Old English grammar videos and reflects on their production and reception.

Rationale: Why make Old English grammar videos?

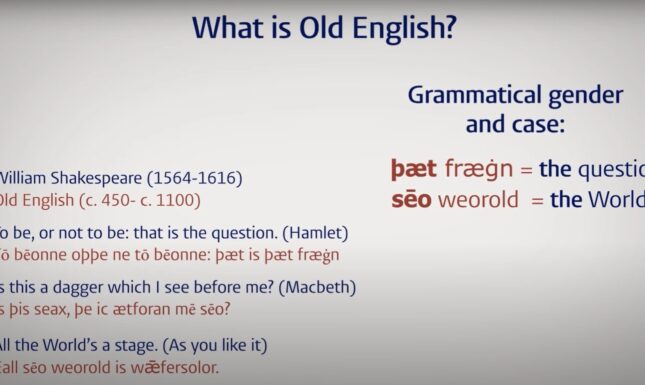

One of the challenges of teaching Old English, the language spoken in England between c. 500 and 1100, is making students understand its grammar. Unlike Modern English, Old English has cases, grammatical genders, strong and weak adjectives and paradigms that are affected by sound changes. Students tend to be a mixed bag, in terms of both interests and backgrounds. Admittedly, most students are drawn to Old English courses for the amazing literature (including the epic poem Beowulf) or the interesting history of early medieval England (Vikings!), while few come into the course with a primary interest in language. As a result, the linguistic elements of the course, whilst crucial for the proper understanding of the source texts, are often the least appreciated by the majority of students. In addition, the students’ educational backgrounds can play a role in their ability to grasp the material – if students speak a language that uses cases (like German, Russian or Turkish) or have been taught one of those in languages in school (incl. Latin and Greek), they will be able to understand elements of Old English grammar more easily; similarly, native speakers of Dutch will be able to recognize various elements of syntax and vocabulary when they are confronted with Old English. In practice, I have noticed that this means that some students will acquire the basics of Old English grammar after one round of explanation, while others may need additional reminders. The challenge of teaching Old English grammar, then, is twofold: it needs to be made interesting and digestible for students without a primary linguistic interest –and– you need to find a way of dealing with the fact that students will acquire elements of grammar at different speeds.

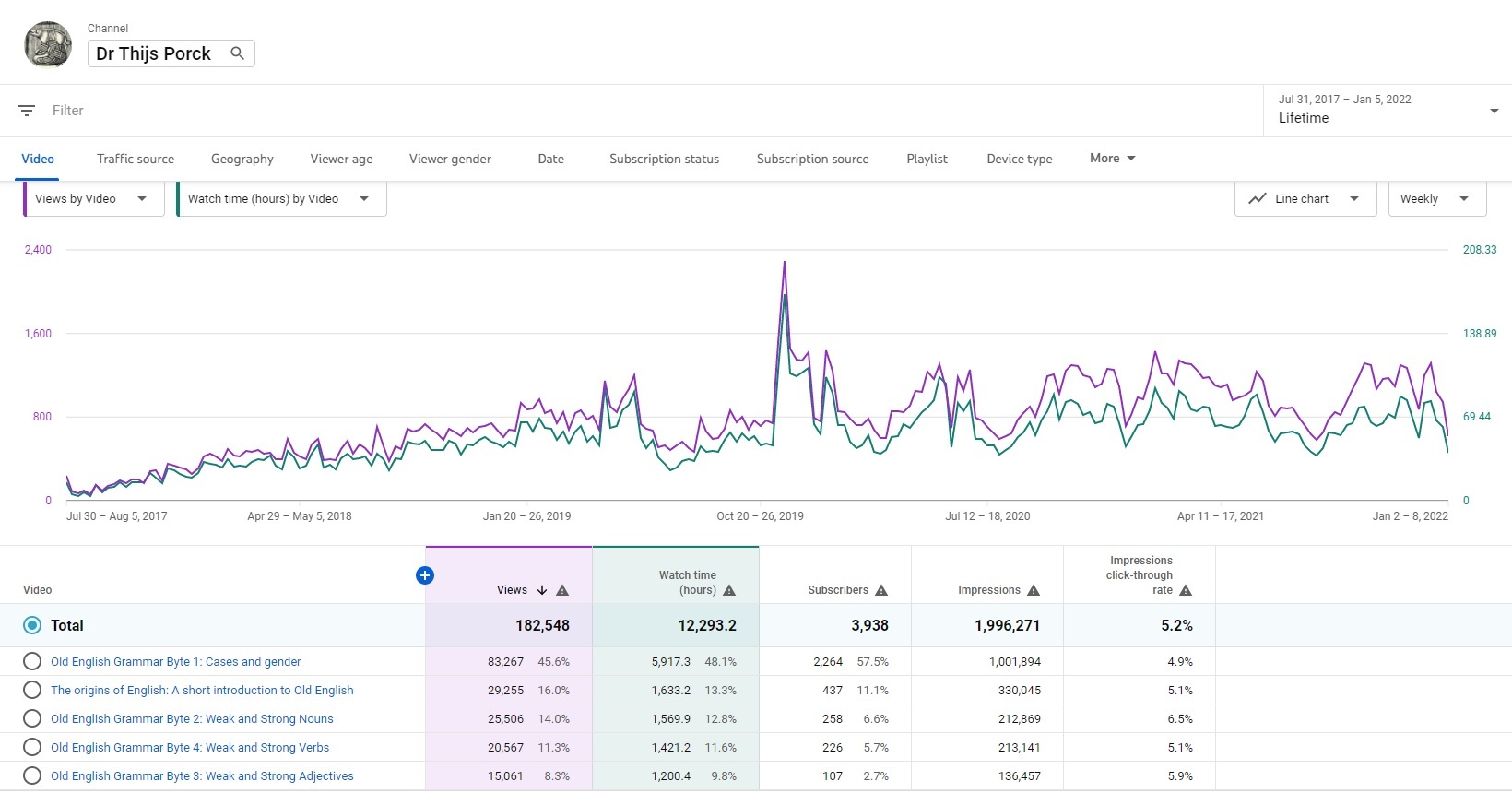

This varying pace of acquisition, in particular, cannot always be catered to in a traditional classroom setting. If I were to repeat the basic grammatical information too often, valuable in-class time is lost and the students who understood it the first time may lose interest, creating a potentially hostile atmosphere for students who need the extra explanation. So, what I really wanted to do was find a way for students to learn Old English grammar at their own pace and avoid having to repeat the same basic information over and over again in class. This is how the idea for Old English Grammar Bytes was born: short upbeat grammar videos that can be watched whenever, at one’s own pace, as often as one might want. The videos were produced with the help of Leiden University’s Expertise Centre for Online Learning, which has a devoted support team for ‘knowledge clips’ (coordinated by Thomas J. Vorisek); since their publication on YouTube, my videos on Old English have been watched over 180,000 times.

Production: Some tips and tricks

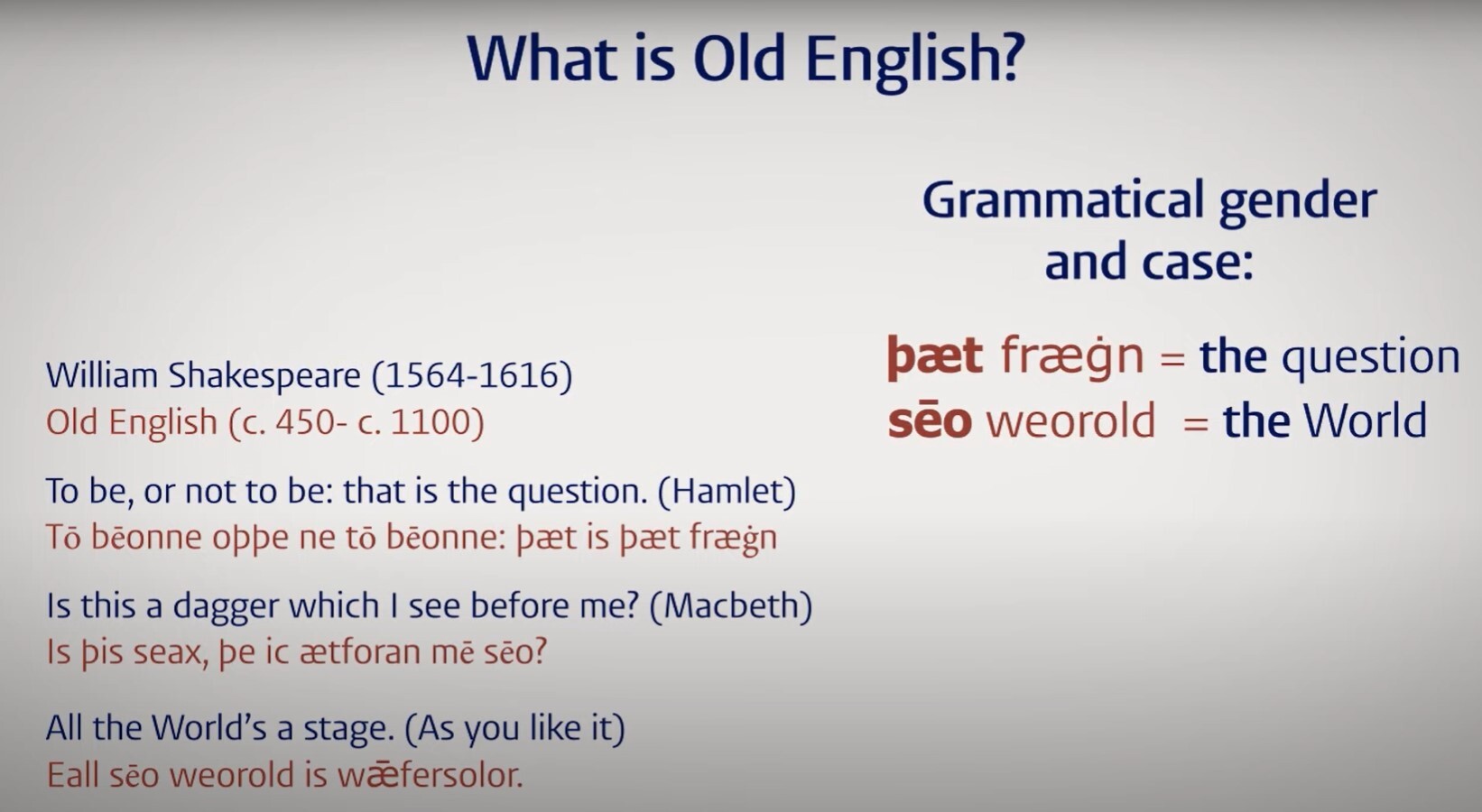

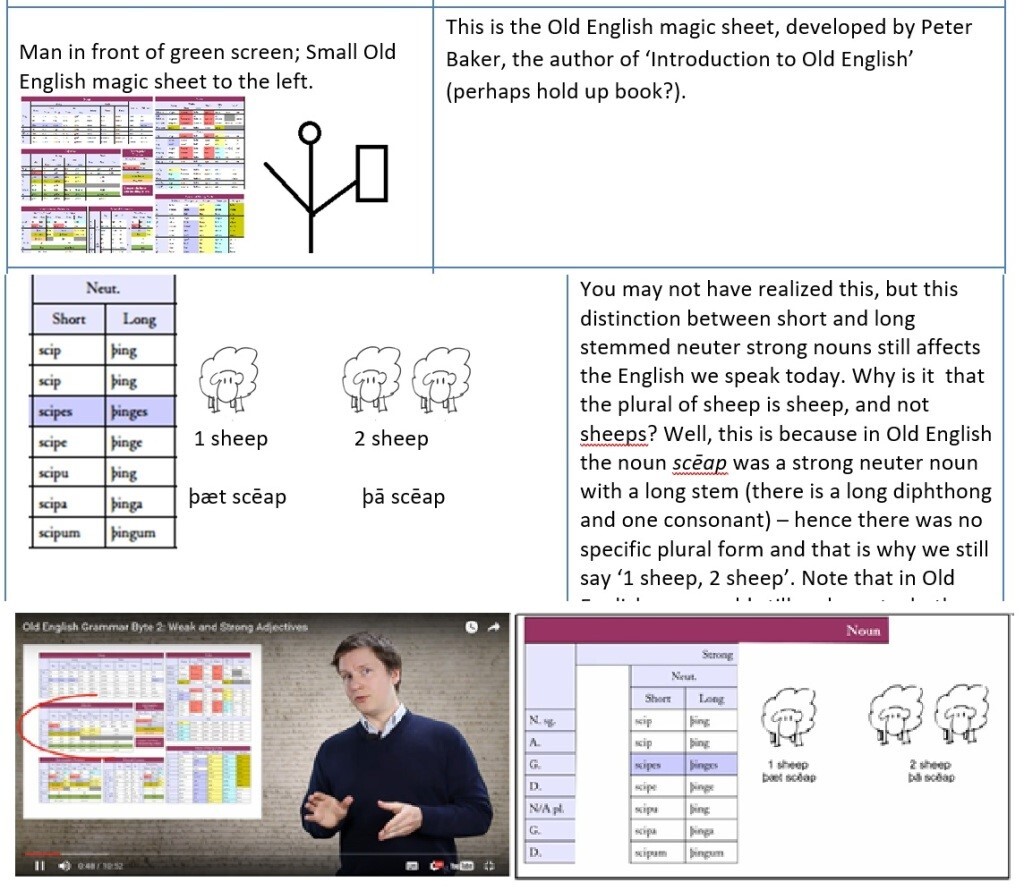

The videos were created using a green screen and fairly simple animations. For each clip, I made a storyboard with, on the left, an impression of what I wanted the image on the screen to look like and, on the right, the text that I wanted to say. As you can see below, in many of the videos, I zoom in on parts of a one-sheet overview of Old English grammar that we also use in our courses on Old English (Peter Baker’s magic sheet of Old English; his Introduction to Old English (3rd ed., 2010) is the coursebook of our 1st-year Old English course, attended by c. 100 students each year).

In setting up and writing the scripts for the videos, I learned that the following six things worked really well for me:

1) Zoom in and add highlights. I quickly found that one of the advantages of using videos to explain grammar is that it allows for a better and more dynamic visualization of information than a traditional classroom setting. For instance, we could zoom in on particular parts of the ‘Magic Sheet’ and, using simple animations (e.g., making a circle appear on the ‘Magic Sheet’), indicate specific forms within the grammatical paradigms.

2) Make it lively. If you watch the videos, you can see me moving my hands and arms quite a bit; a lively presentation style helps to keep the viewer’s attention. When I am not visible, we made sure to use animations to make words appear as I say them, we added pictures and made sure the screen was not static.

3) Liveliness is not just movements and visuals. Enthusiasm is a teacher’s best weapon – one way of bringing that enthusiasm that across is through your voice – avoid being monotonous (e.g., when reading out) and, every now and then, do something different with your voice and/or throw in some audio-effects. As per example, we used a booming voice special effect to distort my voice when I proclaimed a grammatical rule that students often forget “Repeat after me: Whether adjectives are strong or weak is independent from the nouns they modify!” (enjoy that here). This special effect not only refocuses the viewer’s attention to what you are saying, it also helps to hammer the message home. Admittedly, the effect did not prove useful to everyone, given one of the YouTube comments “Please remove the deep voice at 2:49, I was showing this video to my young grandson and he ran out of the room in tears” – apologies!

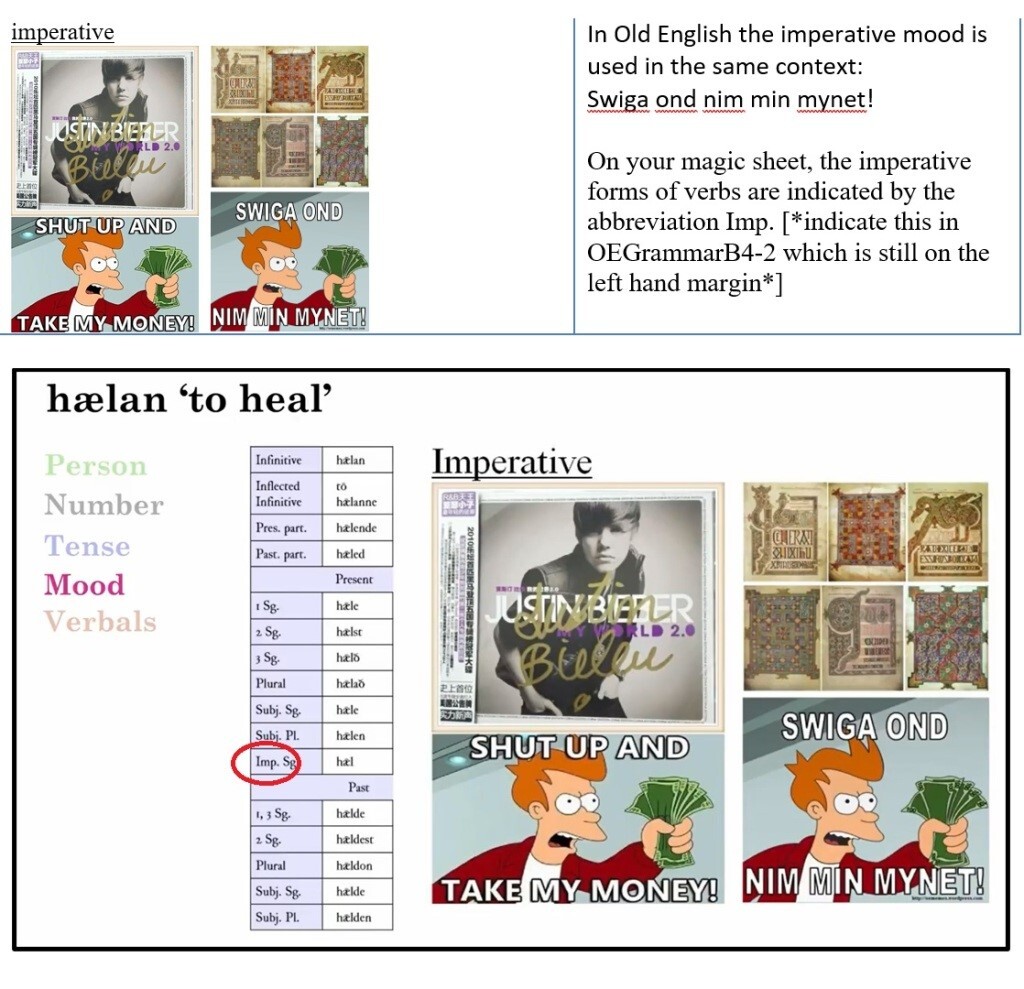

4) Make it light; make it fun. In addition, the ‘dry’ grammatical information could be presented in a light and attractive way by using visual material, including drawings (this video features my own drawings of a dwarf throwing rocks at a dog to explain grammatical functions) and Old English memes (e.g., “swiga ond nim min mynet” perfectly illustrates the imperative mood and is a play on the popular ‘shut up and take my money’ meme – this meme was in vogue at the time of making the video – it is now a classic).

5) Structure, structure, structure. As with any presentation, knowledge clips work best if you make clear what your audience can expect. Start your video by saying hello, give an outline of what the video will deal with (divide the contents into 3 items), and end with a conclusion. Make sure to clearly signal the transition from one part of the video to the next. Another element of structure is the length of the video – do not make it longer than 12 minutes; aim for 8.

6) Be easy to film and edit. In making the videos, I carefully thought about the visuals and special effects, but being a non-native speaker of English, I also had to carefully consider my words: long strings of text with many complex words are likely to trip me up, so I had to adapt my language somewhat in order to avoid having to repeat camera-takes and/or having an editor do a lot of work with cutting and pasting clips. In fact, you will notice that I do not appear too often in the videos, except mostly for the introductions, transitions and conclusions; there is a good reason for this: it is much easier to string together various audio clips than it is to smoothly transition from one video of a person speaking to another in order to get rid of garbled speech. So do not be visible all the time, let the visuals, animations and your voice do the brunt of the work.

The first Old English grammar videos were recorded in 2016 and since then many students have told me that they were very useful. The videos have also helped to reduce time spent explaining grammar in class, creating an opportunity for more thorough discussions of literary texts and devoting time to translation exercises. However, I made sure not to let my own in-class explanations be completely replaced by the grammar videos - after all, students still benefit most from live face-to-face interaction, while the videos remain a good additional resource.

Reception: Sharing educational resources on YouTube

Initially, the videos were only available for students in my own Old English courses via the Learning Management System, but in 2018 I decided to upload four of the videos to my own YouTube channel, followed by three further videos over the last four years. The reception of the videos has been overwhelmingly positive: the videos have been viewed over 180,000 times and they have reached students and language enthusiasts across the globe. According to the channel’s ‘analytics’, viewers have watched a total of 12,300 hours of Old English content via the channel (see below).

For me, the value of bringing the videos to YouTube has been threefold. Firstly, the videos have allowed me to reach a truly global audience, with the YouTube comments revealing that viewers hail from such places as Indonesia, Russia, France and South Korea. The videos have also led to a range of international interactions, including e-mail conversations with Old English enthusiasts from China, Brazil and the US, as well as being invited to give online guest lectures in Costa Rica. Another advantage of the move to YouTube has been the amount of input I have received on the videos; viewers indicate what elements they liked and what aspects of the videos they appreciated less. They also comment on how and why they have used the videos (with many, for instance, revealing they have used the videos to get a better grasp on German!). This is important input for how I plan to make subsequent videos. Last but not least, I have found that the YouTube videos act as a recruitment tool. According to the YouTube analytics, 75% of the viewers of the Old English grammar videos are aged between 18 and 24 years old; as such, this medium caters to a university’s target audience, more so than TikTok, Twitter or Facebook. Indeed, when I taught a summer school in Old English as part of the 15th Leiden Summer School in Linguistics, about half of the 40+ students enrolled in my course indicated that they had become interested in coming to Leiden because of the videos.

As one of the world’s most dominant sources of online information, YouTube can be a place where academics can reach out to a wider, global audience. I hope more academic YouTubers will make their appearance, even if that means they too will have to ask people to ‘like and subscribe’ (which, by the way, you can do here: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCIh0ZR1WZhzhQf5WIkkGeUA )!

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Teachers Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Teachers Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.